‘We believe you harmed your child’: the war over shaken baby convictions | Children

At first, Craig Stillwell and Carla Andrews only vaguely registered the change at the hospital; how the expressions of warm, calm concern in the doctors and nurses who had been helping them look after their sick baby had iced over. It was 15 August 2016, in the early hours of the morning, and their three-month-old daughter, Effie, was fighting for life.

Two hours earlier, Effie had woken up screaming. Her parents, both 23, had no permanent home and were staying at Craig’s father’s place in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire. They had all been asleep on the floor in the lounge: Effie in the travel cot that detached from her pram, Craig still in the uniform he wore as a grass cutter. Carla thought the problem was acid reflux. She passed the baby to Craig and went to prepare a bottle of formula in the kitchen. As she worked, Effie screamed and screamed in the other room. Suddenly she fell silent. Carla heard Craig panic: “Effie! Effie!” She rushed in. Craig, terrified, was holding the child. Effie was white-faced, limbs floppy, eyes fixed, gasping weakly for air.

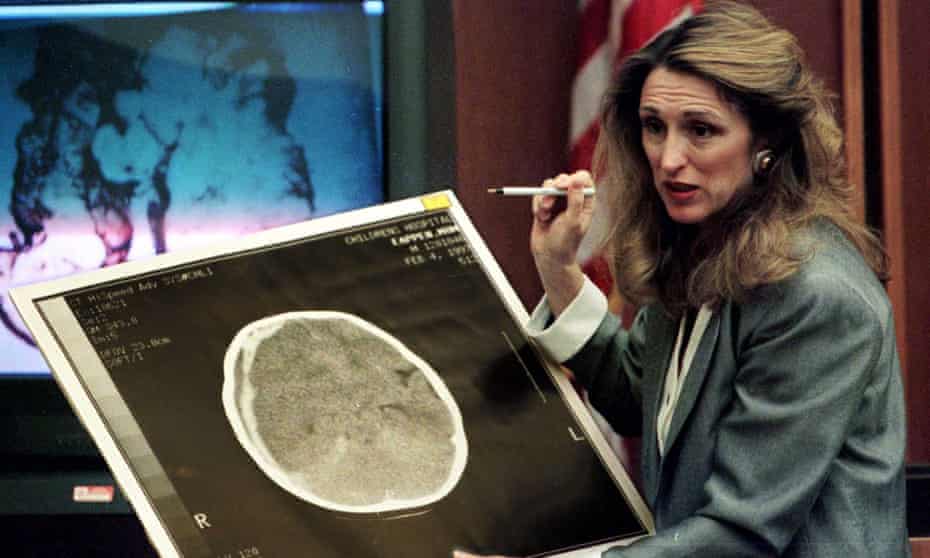

Paramedics arrived at 3.19am, by which time Effie appeared dead. They reached Stoke Mandeville hospital at 3.50am. She roused a little and was taken for a brain scan. Afterwards, in the resuscitation unit, a doctor told them what they had found. Effie had suffered a bleed on the brain, and it didn’t look like it had been the first. Carla and Craig both started crying.

“But how could this happen?” asked Craig.

“We’re going to look into it,” the doctor replied.

At that moment, Craig realised everyone had started treating them with a cold, professional distance. Apart from one nurse, who remained kindly, all the reassuring faces were now hard.

Later that morning, Effie was moved to the high-dependency unit. As the hours passed, the young parents noticed lots of nurses and doctors peering in through the window, staring at them, before hurrying along. At about 3pm, two officers from Thames Valley Police appeared. Craig and Carla were taken to a small room that was empty but for two sofas.

“We believe you’ve harmed your child,” said a detective sergeant.

Craig was placed under arrest for grievous bodily harm. He became agitated. Both parents were told they would be taken in for questioning.

“I’m not going anywhere,” Craig shouted furiously. “I’m staying with my child.”

He tried to run out of the room. There was a commotion. Two more police officers burst in. And then Craig was on the floor, sobbing, his face pressed into the carpet. He felt a steel band lock on to his left wrist. His arm was pulled back painfully.

“I’m sorry,” he cried. “I’m sorry. If you take the cuffs off, I’ll go voluntarily.”

“It’s too late for that,” said the officer.

Back in the ward, Carla went to say goodbye to Effie. Tearfully, she went in for a cuddle. But the one nurse who had shown kindness all day now abruptly intervened.

“You can’t touch her,” she said.

Officers searched their temporary home, removing letters and laptops, while, at the police station, the parents were interviewed separately, each for about three hours. They kept asking Carla: “Could you see Craig when it happened? He’s got a temper, hasn’t he?”

The police were satisfied that they knew what had taken place. Effie’s brain scans told the story. They had shown the three tell-tale symptoms that are believed to be indicative of abusive head trauma, more commonly known as shaken baby syndrome. Experts call these symptoms “the triad”. Effie had brain swelling, bleeding in the eyes, and blood in a protective layer that sits between the brain and the skull called the dura – injuries that can cause blindness, serious disability, epilepsy and, often, death. As the report later filed by the local authority would conclude, they were “likely to be due to an episode of abusive head trauma involving a shaking mechanism”.

Just before midnight, the shattered parents were allowed home. As they stepped out of the police station, Carla nervously and quietly asked Craig, “You haven’t done anything, have you?”

He shook his head. “How could you even think that?”

Despite the certainty with which police, hospital staff and their local authority treated Effie’s parents, the science that underpins shaken baby syndrome is anything but sure. In fact, questions about whether the triad of symptoms found in Effie’s scans are caused by abuse or other innocent events have seen medics, scientists and the police go to war. And it’s a war that is being played out in courtroom after courtroom – with the fate of the accused parents hanging on how well one expert or another happens to make their case.

On one side, there’s the view of the police, prosecutors and the medical establishment: when this triad of symptoms is found, it very strongly suggests shaking, even when other signs that a baby has been aggressively shaken, such as bruising, neck injuries or fractures, are absent. The establishment insists it is solely motivated by a desire to protect babies from dangerous parents; it sometimes characterises opponents as seeking fame, or lucrative expert-witness pay cheques.

On the other side are the sceptics. They insist the prosecutorial forces aren’t concerned with justice so much as courtroom victories. They point to high-profile cases in which triad prosecutions have been overturned, and parents who have been wrongfully imprisoned and had children taken away. They say you can’t look at an x-ray or scan and deduce that a baby has been shaken. According to leading sceptics such as Dr John Plunkett, of the Regina Hospital in Hastings, Minnesota, shaking doesn’t even cause the triad. “You can’t cause these injuries by shaking,” he says. “It’s something else; the kid has banged its head on the ground or there’s some other underlying disease.”

Both sides boast their own authoritative specialists, steeped in the science, many of whom are informed by a lifetime’s clinical or laboratory experience. But the consequences could hardly be more grave. It’s impossible to find accurate figures on charges or convictions, because shaking-related charges are brought in myriad ways, including manslaughter, child abuse, grievous bodily harm, child neglect and so on. It is believed, though, that about 250 shaken baby prosecutions are heard in the UK every year. In the US, the figure is more like 1,500 – and there are thought to be at least five parents currently on death row, awaiting execution for shaking their babies to death.

While the sceptics have an armoury of horror stories about wronged parents, the other side has its own tales of terrible injustice featuring abused babies. Take the case of seven-week-old Ellie Butler. On the evening of 15 February 2007, Ellie suddenly turned white, her limbs became floppy and she started gasping weakly for air. Her father, Ben, rushed her to London’s St Helier hospital. Ellie had no other serious signs of injury, the family had no previous child protection issues. But Ellie showed the triad.

Ben Butler was arrested. In pre-trial proceedings, leading sceptics argued that Ellie’s triad could feasibly be explained by complications triggered by a cyst in her throat. But the scan reportedly showing the cyst was never shown to the trial jury. Butler was convicted of causing grievous bodily harm and cruelty and imprisoned.

Butler appealed. At his 2010 hearing, paediatric neuroradiologist Dr Neil Stoodley argued strongly that Ellie’s injuries were caused by abusive shaking. But his testimony failed. One of the judges called Butler’s conviction a “gross miscarriage of justice”. An article in the Sun (since taken offline) detailed with outrage how Butler and his partner Jennie Gray lost access to their two daughters for five years. Butler complained that his trial only “revolved around medical evidence”. Gray insisted: “If anything, he was an overprotective dad.”

In October 2013, Ellie Butler was killed. A court found that, prior to her death, Ben Butler had subjected her to weeks of escalating violence, leading to a fatal attack that left her with “catastrophic head injuries”. He was sentenced to life in prison. Gray received 42 months after being found guilty of child cruelty and perverting the course of justice. I asked Stoodley, who had argued strongly that Ellie’s 2007 injuries had been the result of shaking, about the moment he heard of Ellie’s death. “I was shocked. Very shocked,” he said. “There was a sense of failure. I felt the medical experts had failed her and the legal system had failed her. I felt we’d all failed.”

The peculiar fact at the heart of the shaken baby wars is that it involves medical professionals establishing whether an illegal act has taken place. It is the diagnosis of a crime. Even when there is no corroborating evidence at all, doctors must decide whether they can spot signs of abuse with enough certainty to make life-changing assertions. Highly technical disputes, involving a subset of a subset of specialists, which would ordinarily play out in the footnoted and caveated pages of academic journals, are being argued in front of judges and juries.

The story of how this curious situation came to be is, in many ways, the story of child abuse and our modern horror of it. It was a moral panic in the late 19th century that led to the creation of organisations such as the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. That spasm of interest was triggered by the sensational 1874 trial of the foster carers of 10-year-old Mary Ellen Wilson, who had been beaten, burned, cut, starved and repeatedly locked in a dark room in their home in Hell’s Kitchen, New York. But public attention soon waned.

It took the widespread use of medical x-rays for the issue of child abuse to surge once again. In 1946, paediatric radiologist John Caffey began to notice strange, recurring patterns on X-rays of infants. They had bleeding in the dura and also repeated bone fracturing. Caffey was mystified. He wrote about this odd collection of symptoms in academic papers. What could be causing it? Scurvy? Rickets? Some strange new infant disease?

As x-ray technology became more common, other radiologists began noting the same patterns. It wasn’t until the early 1950s that some began cautiously wondering if parents might have some malevolent involvement. A few even went as far as to suggest doctors should make subtle and tactful enquiries of the parents.

Then, in 1962, Dr C Henry Kempe published a landmark study in the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association. The Battered Child Syndrome described 302 cases in which an infant had been deliberately harmed by a parent, with one hospital in Colorado treating four cases in a single day. Kempe added a chilling observation: in many cases, he said, “the guilty parent is the one who gives the impression of being more normal”.

At the time, the notion that a parent – especially an innocent-looking one – could deliberately harm their child was subversive and shocking. The editorial in the journal that carried Kempe’s study conceded: “The implication that parents were instrumental in causing injury to their child is often difficult for the physician to accept. But, regardless of how distasteful it may be, the history should be reviewed for possible assault and the necessary laboratory studies performed in order to confirm or reject suspicion.” From today’s perspective, perhaps the most astonishing thing is this astonishment, and the years it took doctors to accept what now seems tragically obvious – that outwardly ordinary parents can indeed be violent or cruel. The shocked response to Kempe’s 1962 study, writes Richard Beck, the author of a history of child-abuse panics, “speaks volumes about the nuclear family’s status in postwar society: the prestige, the respect, and especially the extraordinary degree of privacy that families regarded as their natural right”.

Kempe’s paper fell on the public’s naive notions of the safe and sacred nuclear family like napalm. National newspapers and magazines from Newsweek and Time to Good Housekeeping and Parents magazine ran panicked stories. Popular TV dramas such as Ben Casey and Dr Kildare began including child abuse storylines. Just three years after Kempe’s paper, 300 further studies of child abuse had been published. Soon, every US state but one had introduced mandatory reporting legislation: now, when doctors found evidence of abuse, they were compelled by law to notify authorities. By 1974, 60,000 cases had been reported. Four years later, that number had risen to more than a million.

A specific cause for some of these injuries was suggested in 1972 by a British neurologist. Norman Guthkelch proposed that damage could be caused by the brain being thrown about inside the skull. In 1974, Caffey, the radiologist who had first detected strange symptoms on x-rays back in the 1940s, published a paper describing a “whiplash shaken infant syndrome”, characterised by symptoms detectable on x-rays, such as bleeding in the brain and eyes. “Usually,” he wrote, “there is no history of any trauma of any kind.” Now, when doctors found the telltale signs, there was an emerging body of literature that told them what caused it. The triad became the diagnostic tool for detecting violent abuse.

Meanwhile, across the US and UK, alarm about hidden child abuse was rapidly accelerating. Everyone knew that child-abusing monsters looked like perfectly ordinary-looking mums and dads – and perfectly ordinary-looking mums and dads were everywhere. The 1980s saw the emergence of the “satanic panic”, in which parents and carers were imprisoned for bizarrely deviant crimes. Fran and Dan Keller of Austin, Texas, were falsely accused of forcing children at their daycare to drink blood-laced Kool-Aid and watch the chainsaw dismemberment and graveyard burial of a random passerby. Despite the hallucinogenic insanity of the charges, the Kellers spent 21 years in prison. (The couple were released in 2013 and fully exonerated in June this year.) The UK was not immune to such hysteria. In 1987, 121 youngsters in Cleveland were judged to have been abused, and removed from their homes, many on the basis of a test that judged levels of “anal dilation” that turned out to be associated with other factors such as severe constipation.

By the late 1990s, public scepticism was growing. The accusations had become too wild, journalists were investigating and a number of prosecutions failed. But just as things were calming down, the public’s fascination was reignited by shaken baby syndrome. Attention turned from “satanic abuse” to the possibility that the babies of perfectly innocent-looking caregivers were being violently shaken.

The spotlight fell on shaken baby syndrome following the sensational 1997 trial of a British nanny, 18-year-old Louise Woodward, who was accused and convicted of shaking eight-month-old Matthew Eappen to death at his home in Massachusetts. Matthew’s scans showed the classic triad. Symptom one: bleeding in the dura. This was caused by the tearing, during shaking, of the bridging veins that drain blood from the skull. Symptom two: retinal bleeding. This was caused by tearing, during shaking, within the eye. Symptom three: brain swelling. This was caused by damage, during shaking, to nerve fibres in the brain.

Such injuries, it was said, could only have been caused by shaking, which would lead to the child’s instant collapse. Therefore, the person who was present when it happened was the guilty one. That was Woodward. Under cross-examination, she admitted she had been “not as gentle as I might have been”. It was suggested that she had caused re-bleeding of a previous injury. A jury found her guilty of second-degree murder, and she was sentenced to 15 years to life.

But then something strange happened. After hearing the defence plea for the charge to be changed to manslaughter, the judge accepted that Woodward was not motivated by “malice in the legal sense supporting a conviction for second-degree murder” and reduced her sentence to just 279 days – time served. Woodward was free. In 2007, one leading prosecution witness, neuroradiologist Dr Patrick Barnes, recanted. The injuries, he told reporters, “could have been accidental”. The triad, he had since come to believe, was too readily used as an indicator of abuse. “There is no doubt that errors have been made and injustices have resulted.”

The day after Craig Stillwell was released on bail, a social worker came to call. With Effie still in hospital, they had holed up at Carla’s mother’s house. The visitor wanted them to sign an emergency protection order (EPO), granting the local authority shared responsibility for their daughter. The negotiation might have gone better, but they say the social worker kept calling Effie “Ellie”, even after being repeatedly corrected. Eventually, Carla’s mother had had enough. “You’ve got her name wrong 10 times! Now, fuck off.” He reappeared, minutes after being thrown out, insisting their refusal to sign was irrelevant. “You need to get yourself a solicitor,” he told them. “We’re taking you to court.” The EPO was quickly granted.

Effie was still unwell, but Craig and Carla struggled to get any information about her health. When she suffered a seizure, they weren’t informed until eight hours later. They rushed to the hospital and, Carla says, were forbidden to even look at her through a window. A doctor, citing the powers granted by the EPO, ordered them home.

On 15 September, a weak but recovering Effie was discharged and placed into foster care. Her parents were allowed to see her for 90 minutes three times a week at a contact centre. During those visits, they were watched from across the room by social workers, who made notes about everything they did in their daughter’s presence. Meanwhile, preparations for the family court trial, which would decide whether they would be allowed to have Effie back, had begun. Their solicitor told them about a superstar expert witness. She was brilliant, tough, outspoken and a profound sceptic, having told the BBC’s Newsnight that the science of shaken baby syndrome was “rubbish”. She had also said: “There’s no scientific evidence to support it and there never has been.” The only problem was that she had been struck off by the General Medical Council, following a hearing in which she was found to have dishonestly represented the science at several trials. Her name was Dr Waney Squier.

A paediatric neuropathologist based at Oxford’s John Radcliffe hospital, Squier has studied about 3,000 infant brains and contributed to more than 120 peer-reviewed articles. During the 1990s, when Woodward was being tried, she was a triad believer. Back then, she believed what pretty much everyone did: that the triad is diagnostic of abuse. “I was cheerfully going along saying ‘I agree it’s SBS [shaken baby syndrome]’,” she told me over coffee in the kitchen of her Oxford home. “I went along with the other boys.” As an in-demand expert witness, Squier’s testimony was used in the prosecution of several parents, including Lorraine Harris, who was jailed for manslaughter in 2000 after her four-month-old baby showed the triad. But by 2005, Squier was sufficiently convinced of her error to speak up during Harris’s appeal. Harris was ultimately exonerated. Squier told me she felt “pretty bad” about her part in Harris’s false conviction.

It was some ground-breaking work by neuropathologist Dr Jennian Geddes that first made Squier doubt herself. Geddes’s findings, published in 2001, changed what almost everyone thought they knew about shaken baby syndrome. Previously, the accepted view had been that violent shaking stretches and damages nerve fibres, known as axons, throughout a baby’s brain. When this “diffuse axonal injury” (DAI), occurs, proteins that usually travel along the axons are no longer able to do so. They begin to accumulate, which is what causes the swelling. But Geddes had access to a new technology, in the form of a stain that highlights this axonal swelling in slices of brain by colouring it gold. “I used it on these babies who were alleged to have been shaken [to death],” she says. “The gospel was that they’d suffered DAI, and I discovered that they didn’t really have any axonal damage at all. At least, not caused by trauma.”

Geddes’s work was hugely compelling. Soon a powerful rebellion began to form. Curious experts, in other fields, began finding more and more reasons to doubt the old theory. In the US, the forensic pathologist Dr John Plunkett published work suggesting the triad could be caused by innocent “short falls” – accidental tumbles. Dr Marta Cohen at Sheffield Children’s Hospital and Dr Irene Scheimberg at Barts in London published a paper arguing that dural bleeding and swelling could be the ultimate result of a variety of complaints, from heart problems to sepsis to the re-bleeding of birth injuries.

Doctors began questioning the idea that a baby could be killed by shaking and yet have no other signs of violent attack. “If you grip a baby hard enough to shake it, you’re going to bruise it,” says Squier. “You’re going to fracture ribs, you’re going to break the neck. When babies in a forward-facing car seat are involved in a front-end collision, they get fractures and dislocations in their neck and back. They don’t get shaken baby syndrome.”

Others pointed to the troublesome fact that no witness had ever actually seen a baby being shaken and then suffer the triad. Norman Guthkelch, the British neurologist who’d first mooted the concept, became convinced that rampant injustices were taking place, and became a late-life campaigner against the “dogmatic thinking” of triad believers. It then emerged that John Caffey, who published his influential 1974 paper shortly after Guthkelch, had based his theory about “whiplash shaken infant syndrome” primarily on a Newsweek scare story about an evil nanny who had harmed 15 children and described aggressive winding and shaking in an interview.

Over the years, starting in the 1990s, there was some softening of the idea that the triad always indicated abuse. And then, in 2003, the sceptics were handed another powerful weapon in the form of a brand new paper by Geddes. Colloquially known as “Geddes III”, it described a scenario in which lack of oxygen from something as innocent as choking on something could cause a cascade of events resulting in the triad.

With the arguments against shaken baby syndrome gathering force, the rebellious scientists found themselves increasingly in-demand as expert witnesses. As they strode through courtrooms casting doubt on the science, prosecutions failed and convicted parents were released on appeal.

The prosecutorial forces launched a counter-attack. Their first victory came in 2005, during an appeal hearing against three shaken-baby convictions, including that of Lorraine Harris. Geddes, who admits she doesn’t “find it easy to think on my feet in court”, was cross-examined about her new paper, Geddes III, which was proving useful in overturning convictions. Under heavy questioning about the science, she admitted: “I think we might not have the theory quite right.” The QC retorted: “Dr Geddes, cases up and down the country are taking place where Geddes III is cited by the defence time and time again as the reason why the established theory is wrong.”

“That I am very sorry about,” she said. “It’s not fact, it’s a hypothesis.” She tried to point out that the conventional view of the triad was also just a hypothesis. But it was too late. In their judgment, their Lordships wrote that the theory “can no longer be regarded as a credible or alternative cause of the triad”. The Crown Prosecution Service issued a celebratory press release. Geddes saw the hearing as a calculated attack on her integrity. It was “horrendous,” she recalls. “I was there for two days being cross-examined. It was an attempt to shut my theory down, to prove my research was rubbish and that I was dishonest.”

By whom, I asked.

“I’ve no idea,” she says. “The police. The CPS. I don’t know.”

With Geddes gone, the mysterious forces of “they” still had Squier, Cohen and Scheimberg to deal with. In September 2010, a plan to deal with them was spelled out by a Met Police officer in a Powerpoint presentation. It was witnessed, at the 11th International Conference on Shaken Baby Syndrome in Atlanta, by the lawyer Heather Kirkwood. That year, fully half a decade after it happened, attendees were still celebrating the humiliation of Geddes. “They were making fun of her and doing mock-English accents and misquoting her testimony,” recalls Kirkwood. “It was quite a show.”

But it was a session led by child abuse homicide investigator DCI Colin Welsh that really startled Kirkwood. It was, she says, “a description of the joint efforts of New Scotland Yard, prosecution counsel and prosecution medical experts to prevent Dr Squier and Dr Cohen from testifying for the defence.” As soon as Kirkwood realised what she was seeing, she took out her pad and made frantic notes. Although not necessarily verbatim, they record Welsh explaining shaken baby prosecutions in the UK were in “dire straits”, and that there was a “systematic failure” in securing convictions. Much of this was down to the “same handful of expert witnesses showing up at trial to confuse the jury with the complexity of the science”. The plan was to go after them. Police and prosecutors would question their qualifications, employment history and academic papers to “see if we turn up anything”. Previous court testimony would be combed for potential problems. If problems were discovered, formal complaints would be made.

Back in the UK, Squier had already been targeted. On 23 June 2010, she was at her desk in the hospital, deep into her morning’s work, when she had a disturbing phone call. It was from a barrister with whom she had been working on a case. “Why didn’t you fucking tell me you were up before the GMC?” he demanded. He was calling from court. “Because I’m not,” she said. Squier was baffled. An investigation by the General Medical Council could hardly be more serious. “Don’t be so bloody stupid.”

“Well, this policeman walked into court this morning and told the judge you were,” said the barrister.

The GMC’s paperwork arrived by registered post the next day. “It was awful,” she says. “Absolutely horrendous.” And it wasn’t only Squier. Soon, Scheimberg and Cohen would learn of actions against them.

A body called the National Policing Improvement Agency had formally complained that Squier had dishonestly misrepresented the science of shaken baby syndrome in trials involving six infants between 2007 and 2010. Most of the allegations involved the cherry-picking of evidence, straying into areas outside her expertise and knowingly making statements that were unsupported by the science. The bulk of the GMC hearings took place over six months from October 2015. “The hearing was awful,” she says. “The cross-examination was unrelenting. Thrash, thrash, thrash.” Expert witnesses she had opposed during trials testified against her. “I really thought the prosecution experts were so awful, so arrogant.” The verdict, when it came, was crushing: 130 allegations against her were found proved. Squier, said the judgment, had acted in way that was “misleading, irresponsible, dishonest and likely to bring the reputation of the medical profession into disrepute”. She was struck off. “It was pretty devastating,” she says.

Squier appealed against the ruling of the tribunal. Although the appeal judge agreed that she had failed to work “within the limits of her competence, to be objective and unbiased and pay due regard to the views of other experts,” he crucially decided that she had not been deliberately dishonest. Her removal from the medical register was reversed. She was, however, forbidden from working as an expert witness for three years, by which time she would be at retirement age. As for the other two experts, Scheimberg was cleared after an investigation by the Human Tissue Authority. Cohen’s GMC complaint was dropped.

Ultimately, the plan was a spectacular success. It has been extremely effective in silencing the sceptics and preventing them assisting the defence. “I receive weekly emails about doing cases of shaken baby,” says Cohen. “But I’m not doing them.” It’s said to be increasingly tough finding anyone to speak up for people like Craig Stillwell. One lawyer, Kate Judson, told reporters: “Without Squier, Cohen and Scheimberg, I don’t have anybody to send them to.”

Squier’s opponents are unrepentant. “I was disappointed in the way she was acting in court,” says Dr Colin Smith, a neuropathologist of 20 years’ experience and lead witness at her hearing. “I didn’t think it was good for neuropathology.” He insists that most shaken baby cases are abusive and “relatively straightforward”. So straightforward, in fact, that he doubts the motives of the sceptics. “Whether they truly believe what they are saying, I honestly don’t know.”

And yet the latest scientific evidence seems to support the sceptics. In 2016, Swedish academics published the most in-depth review of the literature on the triad yet, assessing 1,065 papers. What they found was “very low-quality scientific evidence” for the hypothesis that the triad is caused by shaking. Author Niels Lynöe told the New Scientist: “You can’t use these studies to say that whenever you see these changes in the infant brain, the infant has been shaken. It’s not possible according to current knowledge.”

But, Smith argues, you’re never going to see such proof in a scientific study because the only way to scientifically prove shaking causes the triad is to actually shake a baby. And, of course, that’s not allowed. This, he argues, is why you must also look at the evidence from clinical practice. Take the argument that “short falls” can cause the triad. That’s a nice theory but, in real life, “you only get the triad from such a fall when no one else is watching”. When there are witnesses to a fall, you typically find a very different pattern of bleeding as well as fractures. “And that is not the triad,” he says. The same goes for sepsis, heart complaints and the theory that oxygen starvation caused by choking can lead to the triad. “There isn’t a single witnessed choking case that looks anything like this,” he says.

Smith used research by Geddes to explain one idea of how shaking did lead to the triad. The conventional view used to be that it caused widespread damage to the axons in the brain. Geddes revealed this widespread damage was absent. But she did find that shaking could cause highly localised axonal damage. “It happens where the brain meets the spinal cord in the neck,” says Smith. “If you imagine the head flopping about uncontrolled, this is where Geddes described the damage, exactly at this point where the head twists about. This is where the centres that control heart function and respiration are.”

Another formidable force at Squire’s GMC hearing was Stoodley. I arranged to meet him in a cafe opposite St Pancras station in London. He had arrived from giving evidence at a shaking trial in Essex. Of the nearly 900 cases of triad babies he examined, he concluded that about 90% were caused by abusive shaking. Of that 90%, “about 10% are wilful and persistent abuse, and that leaves 80% when, in my view, the injury occurs as a result of a momentary loss of control”.

What this implies is that the majority of such cases involve no other injuries. No bruising, no neck injuries, no fractures or breaks. How can he be sure they have been shaken? “Virtually all these injuries occur when the child is with a single carer,” he says. “It’s not witnessed by anyone else. The holy grail of lawyers is to find a naturally occurring medical condition we’ve been missing all this time that causes it. Let’s assume there is one. Most diseases tend to occur at different times of day. This one would have to be somehow sentient and know the child it’s about to cause trouble with is in the care of a single carer.” But this argument is wholly circumstantial, I protest. “Well it has to be,” he says. “We can’t do the relevant experiments.”

Stoodley has another powerful argument. In his day-to-day work at a major children’s trauma centre, he sees the triad occurring in concert with other obvious signs of abuse: “multiple fractures, bruises, burns, scalds”. But what about the earlier Geddes work that implies even light shaking could cause it? Doesn’t this show the triad could stem from innocent falling, or shaking so mild you couldn’t reasonably call it abusive? “Humans just wouldn’t have survived if we were that fragile,” he says. But babies bruise easily. “Correct.” How come we don’t see bruising in so many cases of apparent shaking? “I don’t know,” he says. “But if you have a momentary loss of control, why would that cause bruising?”

The triad believers argue that defence lawyers have been cynically seeking new and alternative causes of the three tell-tale injuries. “They move about,” says Colin Smith. “There’s been rickets, vitamin D deficiency and now there’s Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.” EDS is a rare genetic disorder of the connective tissues, the vascular form of which can trigger rampant bleeding. But Smith is dismissive of it being a cause of the triad. “Show me one single case,” he says. “They just don’t exist.” Instead, “many of these cases have a very typical scenario. It’s a young mother or father, very poor social support around them, often limited education, and baby just won’t stop crying and they snap for one second.”

When Craig Stillwell hired a solicitor who specialised in cases like his, she asked him: “Have you heard of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome?” Stillwell and his partner, Carla Andrews, had found Rachel Carter, of the firm Wollen Michelmore, after a Google search for “shaken baby”. “A lot of her cases came up,” says Carla. She saw repeated references to EDS. “I don’t know what it was, so I gave them a ring.” Indeed, Carter, founder of parentsaccused.co.uk, is arguably one of the lawyers best known for using the EDS defence. In 10 years of practice, she says, she’s had “10 to 12” EDS clients, “and they’ve all been within the last couple of years”.

Carla paid £250 for blood tests. By Valentine’s Day 2017, all the results had come in. Both Carla and Effie had EDS. It made sense to Carla. “It answered so many questions I had about myself,” she says. Carla bruises easily and spectacularly. Months earlier, she had posted a photo to Facebook jokingly complaining about a nurse who had “missed” while trying to insert a cannula. Almost her entire forearm was brown and blue. When Carla phoned her own solicitor to tell him about the genetic test, he was delighted. “We’re going to win,” he announced. It was the first encouraging news they had had in a long time. Living without Effie was “absolutely horrible”, says Carla. “I always woke up at three in the morning because that’s when she used to wake up.”

“Then I’d wake up hearing Carla crying, which was heart-breaking,” adds Craig.

In April 2017, the family court took evidence from six expert witnesses, including haematologist Dr Russell Keenan, who testified that Effie’s condition could lead to spontaneous bleeding “with no trauma whatsoever”. The judge ruled that Effie’s collapse was “most likely the consequence of a naturally evolving disease”. She praised Craig and Carla’s “maturity and restraint” and acknowledged the “unimaginable horror” they had lived through. Effie is now back with her parents and thriving.

But one expert witness was unmoved by Carla’s diagnosis: Stoodley. “He was horrible,” says Carla. “He was always saying all this negative stuff and making it seem like it was fact.”

“He was all for saying it was shaken baby [syndrome],” Craig says.

Stoodley remains convinced Craig and Carla’s baby was shaken. “That was the conclusion I came to and I’ve not been made aware of anything since my judgment that would make me wish to alter it,” he said. “I’m not aware of any clinical evidence to support EDS as being causative of this pattern of injury.”

Today, 16 years after Geddes published the paper that convinced Waney Squier she was wrong, and two decades after the awful drama of the Louise Woodward trial, the war continues. Prosecutors have silenced their most powerful courtroom enemies, and influential scientists continue to cast doubt on the science of the triad, while experts such as Colin Smith use compelling clinical evidence to convince judges and juries that the triad is, indeed, strong evidence of abuse.

And for Stoodley, too, the facts are as certain as they have ever been. But, surprisingly for a man who has testified against hundreds of parents, he confesses to profound doubts about the justice of putting them in prison. “There should be something else on the statute book, like aggravated manslaughter, to allow more nuance,” he said. And that charge shouldn’t necessarily lead to a custodial sentence. “I’m not sure locking people up is the answer. I think the worst sentence society could impose on a parent who had just lost it for a moment is watching your child grow up handicapped because of something you knew you had done.” When he was a baby, he says, he cried all the time. “My mother always said she was amazed I survived infancy.” He smiles ruefully. “Most of us who are parents have been pretty close to it, I suspect.”

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here.